The Next Nuclear Age?

So much has changed in 80 years, but at least one thing has not: in 2025, we still find ourselves grappling with the same urgent need for awareness and action when it comes to nuclear policy.

It’s been eight decades since FAS’s founders – a group of scientists and engineers who worked on the Manhattan Project – came together after witnessing the effects of the first use of nuclear weapons.

The landscape of nuclear risk has significantly changed, with only one major nuclear limitations treaty remaining and that set to expire in February 2026.

Countries with nuclear capabilities are no longer disarming. Instead, they are modernizing and expanding their arsenals.

The ongoing conflict in Ukraine further exacerbates these risks, while geopolitical tensions, such as China’s military advancements and Europe's military assertiveness, add to the instability.

It’s against this backdrop that FAS embarked upon a partnership with The Washington Post, unlike anything in our organization’s history.

Synthesizing its extensive and internationally-renowned open source research, FAS’s Global Risk team joined forces for a series of opinion pieces, providing insights into the current state of global nuclear arsenals, the actors involved, and the potential for catastrophic consequences arising from accidents or misjudgments.

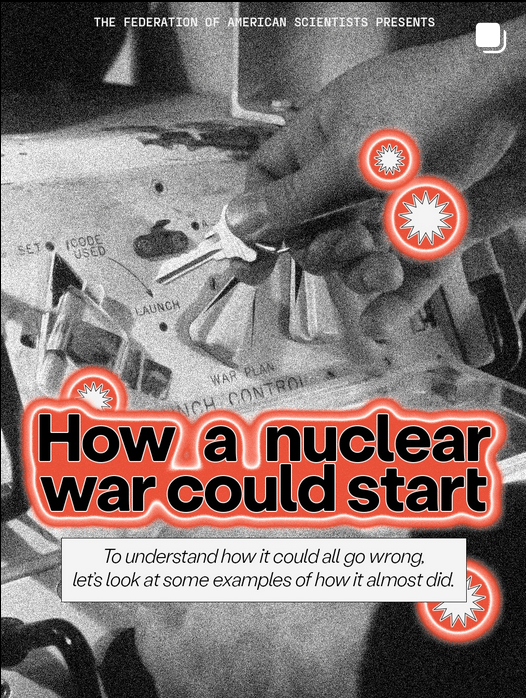

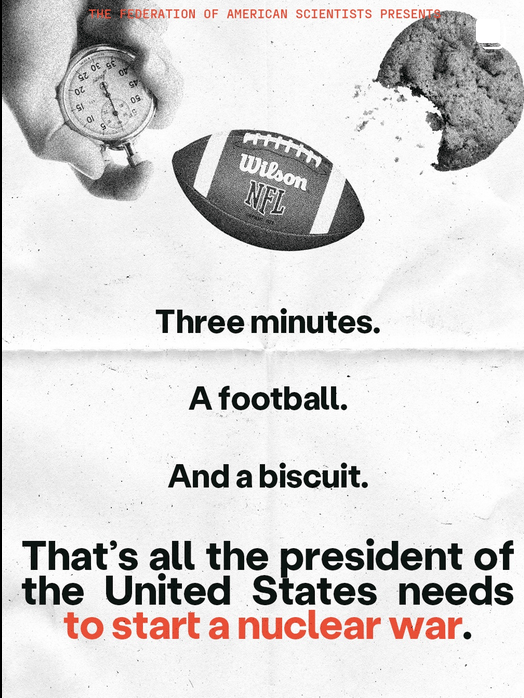

Notably, it highlights the alarming fact that in the U.S., the president can initiate a nuclear strike within just three minutes, underscoring the gravity of the decision-making process.

This series aimed not only to inform but to inspire policy change. It brought world-class data and policy implications into clear focus, deepening public understanding of the stakes involved as nuclear-capable states shift their stances and policies.

As Jon Wolfsthal, FAS Director of Global Risk – and a co-author in the series – so keenly put it, this series “enabled the public to appreciate what the expert community has known for several years: we are now in a new nuclear arms race.”

Each week, the series tackled daunting scenarios, making them accessible to readers across various formats—print, digital, or social media.

Collaborating with the Post’s creative and experienced staff, and leveraging the immense reach of an internationally known publication, FAS’s team produced visually stunning and thought-provoking work that both built on FAS’s legacy of leading nuclear policy discussions and introduced new audiences to what’s really at stake when it comes to nuclear weapons.

“It’s the importance of putting out information about these issues, to raise the nuclear IQ with people,” Hans Kristensen, Director of FAS’s Nuclear Information Project (and another of the series’ authors) said of the series. “Without information, without factual information, you can’t act. You can’t relate to the world you live in.”

Building off of this unique collaboration, in 2026, the team continues to look for innovative ways to inform the domestic and international discourse around nuclear weapons, and engage with new audiences. It’s work that’s essential both for decisionmakers in government, and for citizens still grappling with the contours of this new nuclear age.